When construing a statue, judges can be quick to shift responsibility to the legislative branch. Many litigators have heard from the bench that their argument is with the Legislature, not the Court. This oft-heard statement exemplifies the legal fiction that the Legislature is aware of how our appellate courts construe their statutes and will make corrections, if necessary. Indeed, our courts sometimes take the Legislature’s failure to act as tacit approval of the court’s interpretation.[1] Despite this comforting fiction, lack of success in the courts rarely leads to legislative intervention.

The problem created by the Court’s interpretation of A.R.S. § 25-409(C) in Sheets v. Mead—that a child who was adopted can never be subject to court-ordered third-party or grandparent visitation—is one of those rare instances in which the legislative branch was able to take corrective action. Sheets, 238 Ariz. 55 (App. 2015). Since Sheets, children who were adopted by “single” parents received disparate treatment relative to children who were born “out of wedlock.” The Court ruled in Sheets that it lacked the authority to award visitation with an adopted child because of the interaction between A.R.S. §§ 8-117 and 25-409. The judge’s hands were tied: because third-party visitation is purely statutory, the only way to change the outcome would be to amend the law. The legislative fix, SB1323, will go into effect on September 24, 2022. This is the story of Sheets and how a collaboration between attorneys and legislatures led to an extraordinary result.

Sheets v. Mead

In 2010, Bonny and Lori, a committed same sex couple, were fostering two children together with the aim of adoption and were in a catch-22. As foster parents, they had joint access and legal responsibility for each child. But Arizona did not permit joint adoption by same sex couples. To adopt these children and bring them out of the foster system, each could have only one legal parent. So, the adoption papers listed Bonny as the legal parent of the boy and Lori as the legal parent of the girl. There was no question that, despite the adoption papers, the couple intended to jointly raise the children as a family unit.

After Bonny and Lori’s relationship ended, Lori refused to allow Bonny access to her daughter. Because Bonny was not the child’s legal parent, she petitioned for access under A.R.S. § 25-409(C)(2), which allows the court to order visitation for a person other than a legal parent where the child was “born out of wedlock” and the child’s legal parents are not married to each other when the petition is filed. Because Bonny’s daughter did not have married legal parents when she was adopted, the family court ruled she was eligible for visitation and granted Bonny access to her daughter.

The Arizona Court of Appeals reversed. There is a separate statute that says, upon adoption, legal rights of parent and child exist as though the child were born to the adoptive parent in lawful wedlock. A.R.S. § 8-117(A). In Sheets v. Mead, the court ruled that the single-parent adoption changed the child’s legal status to having been “born in lawful wedlock” despite no actual marriage existing at the time of the adoption. It held that a child who is adopted before a visitation petition is filed is not eligible for nonparent visitation under § 25-409(C). Acknowledging its holding leads to “counterintuitive results,” the court insisted the Legislature has sought to ensure that “adoptive parents enjoy a status equal to that of biological parents.” Sheets, 238 Ariz. at 58 (Ariz. App. 2015) (quoting In re Maricopa Cnty. Juv. Act. No. JA-502394, 186 Ariz. 597, 599 (App. 1996).

Although the goal of equalizing the treatment of adoptive and biological parents is laudable, Sheets had the opposite effect and led to more “counterintuitive results” than perhaps the court had in mind. Initially, many believed that Sheets would mostly affect same-sex couples who were unable to jointly adopt children before Obergefell. But Sheets’ holding has come to negatively affect all kinds of people, particularly grandparents seeking visitation with their adopted grandchildren.

Challenging Sheets v. Mead

After Sheets, if one party adopted a child, neither the non-adopting parent nor the grandparents could petition for visitation if the couple separated, the adoptive parent died, etc. The same result would occur if one party adopted prior to their marriage and then had a biological child with their new spouse. One child would enjoy time with both parents under a typical parenting plan while the other would be legally considered the “born in wedlock” child of the adoptive parent and no one else. Doty-Perez v. Doty-Perez II, 245 Ariz. 229 (Ariz. App. 2018). This has led to tragic consequences, leaving non-adoptive parents and grandparents with no ability to seek court-ordered visitation and forced to rely on the assent of the legal parent no matter how close their relationship with the child. Often, the non-adoptive parent will be barred from ever seeing the child again notwithstanding the child’s best interests.

The holding of Sheets was first challenged in Doty-Perez v. Doty-Perez II. Id. at 235. Like in Sheets, the parties in Doty-Perez II were prohibited from jointly adopting children in Arizona, so they agreed that one of the parties would be the adoptive parent.[2] When they divorced, the non-adoptive parent petitioned for third-party visitation under A.R.S. § 25-409(C)(2). Susan was denied visitation because, consistent with the holding in Sheets, the adopted children were considered to be born “in lawful wedlock,” despite Tonya adopting them as a “single” parent. The superior court ruled in favor of Susan having visitation, finding 25-409(C)(2) unconstitutional as applied because it treated adopted children differently than other children based exclusively on their status of having been adopted.

On appeal, Susan argued that the § 25-409(C)(2), as construed by Sheets, unconstitutionally treated adopted children differently from biological children. If the children had been naturally born to Tonya when she was unmarried (“out of wedlock”) or when she was married to Susan (“in wedlock”), Susan would have had no difficulty petitioning for visitation rights. The Court rejected these arguments and declined to overturn Sheets. Acknowledging the consequences of Sheets, the Court noted “potentially harsh results could also occur [as a result of Sheets] in opposite-sex marriages and in both same- and opposite-sex unmarried relationships . . . however, absent a constitutional infirmity, it is for the Legislature not this court to make those policy determinations. Doty-Perez II, 245 Ariz. at 235.

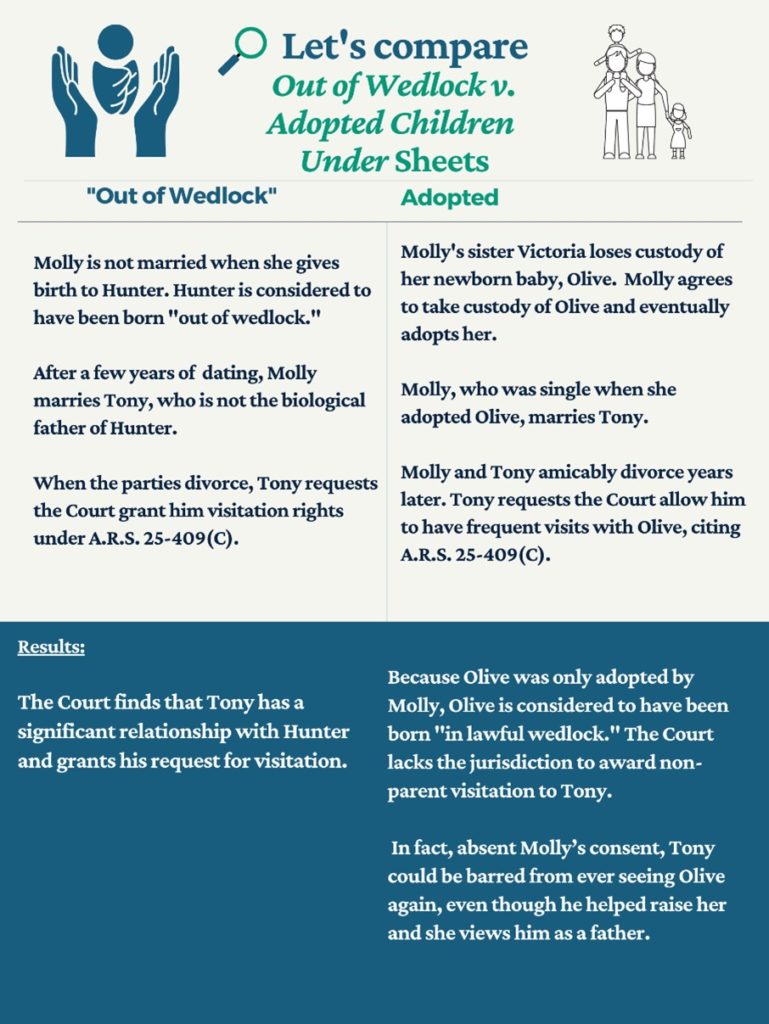

Unintended Consequences of Sheets [see chart below]

The holding in Sheets, combined with the prohibition on same-sex marriage and adoption, led to many children being adopted by “single” parents despite being in committed relationships and intending to coparent. These children, despite being raised by two parents, were legally separated from their non-adoptive parents when the relationship ended. They were then barred from having visitation together. As a result, these “lost children” were denied access to someone they viewed as a parent—children do not generally appreciate the distinction between a “legal” parent and any other parent who raised the child as such.

But it was not just the children of same-sex couples who were affected by the Sheets decision. Grandparents were barred from petitioning for visitation over the children, even if they had a stable, developed relationship with them, because a child adopted by a single person was treated as “born in lawful wedlock” and therefore ineligible. Fathers who discovered that they had produced a child out of wedlock were similarly barred after an adoption even if they had developed a relationship with the child at the adoptive parent’s behest. The legislature could not have intended to segregate adopted children in these unforeseen ways.

A Legislative Solution

After Doty-Perez II, it had become abundantly clear that there would be no judicial remedy for the Sheets problem. The only remaining avenue was, as the Court of Appeals declared in Doty-Perez II, a bill to amend § 25-409.

During the 2020-2021 legislative session, Arizona District 29 Senator Martin Quezada sponsored a bill that would clarify the statute to treat children adopted by a single parent the same as a child naturally born to a single parent (and the same for children born to or adopted by a married couple). Due in large part to the COVID-19 pandemic turning the Legislature’s focus elsewhere, the bill was never heard in committee.

After the close of the 2021 legislative session, a family affected by the Sheets decision came forward and met with District 8 Senator TJ Shope. In their family, the grandparents were fortunate in that they were able to spend time with their two grandchildren—one adopted and one naturally born during their daughter’s marriage—but they knew that circumstances could change anytime. A.R.S. § 25-409, as interpreted in Sheets, would allow them to seek a court order for visitation with their “naturally born” grandchild but not with the adopted one. Senator Shope agreed to sponsor the bill and worked together with Senator Quezada to make solving this problem a priority.

SB1323, introduced in the 55th session of the Arizona Legislature, amends § 25-409 so that, for purposes of visitation, an adopted child is treated as though born in lawful wedlock if the child is adopted by a married couple, and a child adopted by a single person is treated as though born to a single person. The bill simply and directly addresses the inequitable treatment of adopted children, guaranteeing that they are treated the same as other children with similar “birth” statuses. The bill passed through every committee and floor in both chambers without a single opposition vote. SB1323 will take effect on the general effective date in 2022, over seven years after Sheets was decided.

SB1323 will theoretically make visitation available to would-be petitioners—grandparents and other third parties with significant relationships with the child—who were previously barred by Sheets. Of course, the practical problem is significant time will have passed since the last time they saw the child. Proving that visitation is in the child’s best interests without having had visitation in years will be challenging if not insurmountable. Some of these children are now adults, having reached the age of majority while Sheets remained in effect and are no longer subject to Title 25 at all.

For many of the families affected by the Sheets opinion, the passage of SB1323 is bittersweet. Some lost many years that they could have spent with their children or grandchildren they raised as their own. Many of those children went through their teenage years while an important parental figure was missing from their life. The bill cannot bring these people back to 2015 to relive the children’s minority years, but it will prevent the same harm from befalling other families in the future. SB1323 represents the legal system working, albeit slowly, to align the law with the unique facts and circumstances of real families. If nothing else, the bill should serve as an example that when a judge instructs a party to take their case to the legislature, perhaps they really can.

[1] See, e.g., Jeter v. Mayo Clinic Arizona, 211 Ariz. 386, 121 P.3d 1256 (Ct. App. 2005) (recodifying a statute without addressing the court’s construction leads to presumption that Legislature knew of and approved the court’s decision).

[2] The parties were married in another state but, at that time, Arizona did not recognize their marriage and therefore did not allow them to jointly adopt. See A.R.S. § 8-103(A).

This article was initially published in the Arizona Attorney magazine on February 1, 2023.

MARKUS RISINGER is an attorney at Woodnick Law, PLLC and MLS faculty associate teaching administrative regulation at the ASU Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. He practices in all aspects of child welfare matters, including Title 8 dependency/severance, Title 13 defense litigation, Title 25 parent and third-party rights, Title 41 administrative controversies, and appeals.

TAYLOR C. YOUNG has been handling complex family law appeals and other civil appellate litigation in Arizona for over 20 years. After clerking at the Arizona Supreme Court and honing his skills in the appellate departments of several prominent Phoenix firms, Taylor launched his own appellate boutique firm in 2012. He holds an AV Preeminent peer rating from Martindale-Avvo and is included in The Best Lawyers in America in the area of Appellate Practice. When not lawyering, Taylor often can be found teaching legal, business, and non-profit groups on topics such as legal process, writing skills, and political advocacy.

ISABEL RANNEY is a third-year law student at the ASU Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at ASU and associate editor of The Law Journal for Social Justice. She has been a law clerk at Woodnick Law, PLLC since the summer of 2021.