Gregg Woodnick: I was in the earlier stages of my legal career when I represented minors seeking an abortion through the judicial bypass statute. My job was to meet these young women briefly prior to their appearance before the judge in the small room at the Courthouse just outside the court room. Often, I knew nothing about them besides their first name, age, and that they wanted an abortion.

I feel thankful to say that I only had pleasant experiences. I heard horror stories from other attorneys of minors who bravely mustered the courage to ask the judge to allow them to terminate their pregnancies and who got denied, if not shamed, as a result. I never had that outcome; all of the minors I represented were granted their abortions and you could instantly feel the relief in the room. This young thirteen or fourteen some old child no longer had to carry the stress of the pregnancy or the anxiety of having to tell their parents or guardians.

I think what helped immensely was that part of the process involved the minors meeting with a licensed counselor before they met their attorney so that the minors were emotionally prepared to go before the judge. This is how I met Mysti Rainwater.

Mysti Rainwater: I was hired by Planned Parenthood to counsel many clients, including minors who had decided to terminate their pregnancies without their parents knowing.[1] Planned Parenthood never advocated abortion as a form of birth control and my job was to educate clients of the importance and availability of birth control. Specifically, I was trained to explain three options for an unplanned pregnancy: (1) pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting, (2) pregnancy, childbirth, and adoption, and (3) abortion. For those seeking judicial bypass, my role was to make sure these young girls were emotionally prepared to go before the judge to request abortion authorization.

What really struck me was the deep-seated fear these children had about becoming homeless as a result of their pregnancy. I call it the “Triple Whammy:” the minors often relayed that they did not want to tell their parents or guardians about the pregnancy because of the fear of being thrown out by their parents if (1) they find out they are engaging in sexual activity, (2) they find out they are pregnant, and/or (3) they find out they had an abortion. Although only a small number of children are actually kicked out by their parents, these pregnant minors tended to be deeply concerned that they would face homelessness if their parents found out.

I was employed by Planned Parenthood until it closed its counseling program nationwide in 2006 (probably due to a lack of funding). My work there and with those young girls has stuck with me and I was interested to see how the judicial bypass process had carried on after Planned Parenthood ceased providing the counseling services and how the Dobbs ruling would impact the availability of the process.

Legislative Background

A judicial bypass is a confidential legal process by which a minor can obtain an abortion in the absence of parental consent or knowledge at no financial cost to themselves. A.R.S. § 36-2152(B). Arizona enacted its current judicial bypass statute in 2000, after several decades of attempts to refine the language of the statute in light of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Belloti v. Baird, 443 U.S. 622 (1979) (“Bellotti II”). In Bellotti II, the Court set forth four (4) factors that must be considered in determining whether a minor can receive an abortion absent parental consent. These factors require that a pregnant minor show (1) “she possesses the maturity and information to make her abortion decision,” (2) if she cannot make the decision herself, an abortion is in her best interests, (3) the procedure insures “the minor’s anonymity” and (4) “courts must conduct a bypass procedure” quickly to allow the minor to obtain the abortion. Planned Parenthood of Southern Arizona v. Lawall, 307 F.3d 783 (9th Cir. 2002) (citing Bellotti II, 497 U.S. 502 (1990)).

Arizona’s statute, A.R.S. § 36-2152, incorporates these factors. To obtain a judicial bypass, a superior court judge must find that the pregnant minor is “mature and capable of giving informed consent.” A.R.S. § 36-2152(B). If the judge finds that the minor is not mature or is incapable of giving informed consent, the judge must consider whether authorizing an abortion in the absence of these factors and parental consent is in the best interest of the minor. Id. In Arizona, a minor seeking a judicial bypass is entitled to free legal counsel and the Court must appoint a guardian ad litem for them. A.R.S. § 36-2152(D). The entire process is confidential, and the Court must hold a hearing and issue a ruling within forty-eight (48) hours after the Petition is filed (excluding weekends and holidays). A.R.S. § 36-2152(E), (F). A minor who is denied a judicial bypass is entitled to an appeal, which must also be heard and ruled upon within forty-eight (48) hours.

A minor who claims to be mature must prove the same by clear and convincing evidence, which is based on their “experience level, perspective, and judgment.” A.R.S. § 36-2152(C). To make this determination, the Court may consider the minor’s age, work experience, ability to handle personal finances, as well as factors that go toward the minor’s perspective and judgment, such as the extent to which they considered their options and their conduct after learning of their pregnancy. Id.

Neither parental consent nor judicial authorization is required if the minor informs an attending abortion provider that the pregnancy was the result of sexual conduct with an adult (familial or in a parental status) or person residing in the “same household with the minor and the minor’s mother.” A.R.S. § 36-2152(H)(1). Nor is parental consent or a judicial bypass required if an abortion is necessary to prevent death or the risk of “substantial and irreversible impairment of major bodily function” of the minor. A.R.S. § 36-2152(H)(2).

What is a Judicial Bypass Really Like?

For those who learn about the judicial bypass process and are able to retain free legal counsel, the idea of standing before a Judge and proving they are mature enough to terminate their pregnancy is terrifying (as it would be for anyone, let alone a seventh-grader). This is where Mysti’s role was imperative.

Mysti recalls the story of a 15-year-old Catholic female, Jane Doe, whose situation embodied the “Triple Whammy.” Jane expressed to Mysti that her parents would completely “freak out” to discover (1) she was having sex, (2) she was pregnant, and (3) she wanted to choose an abortion. During this conversation, it was Mysti’s job to determine what the actual risk to the client was. Was Jane actually at risk or would she simply disappoint her Catholic parents? Ultimately, Jane was granted the judicial bypass, as she could competently articulate there was a strong likelihood that she would become homeless if her parents discovered that she was pregnant.

Another young girl, 17, had just received a full-ride to a University and believed her future would be jeopardized if she were forced to continue the pregnancy. Like many of the young girls Mysti spoke with, she was accompanied by her boyfriend, who wanted her to continue the pregnancy. After Mysti explained the options and the statistics of actually placing for adoption following pregnancy, the boyfriend supported her decision to choose an abortion. The girl also had evidence to share with the judge that her parents, for religious reasons, would not consent to the procedure.

Given the private nature of the bypass process and the interest in protecting the anonymity of the minor, there is limited data available showing the demographics of the minors who request a judicial bypass. However, according to a 2021 study conducted on Judicial Bypass’ in Illinois, the majority of minors seeking a bypass are 16 or 17 and go through the bypass process out of fear of being forced to continue the pregnancy and of being kicked out of their home and/or cut off financially.[2] Additionally, the study indicated that the majority of minors were between three to twenty weeks pregnant, with the average being around nine and a half weeks pregnant by the time of their scheduled abortion appointment. Id.

Judicial Bypass in Arizona in light of S.B. 1164 (2022) and Dobbs

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs does not overturn Bellotti II. The standard set forth in that ruling remains good law and will remain precedent for states that choose to retain the judicial bypass process. Without legal abortion access, however, the judicial bypass process becomes moot.

What will happen in Arizona—to abortion access, to judicial bypass—remains uncertain. On one hand, there is S.B. 1164 (2022), which became effective on September 24, 2022. A fifteen-week abortion ban is far from ideal, as most abortions are done during the first trimester and after that usually due to a fetal anomaly or other major defect discovered as the pregnancy developed. Nonetheless, some individuals may see it as a sigh of relief to still have abortion as an option, if only briefly into a pregnancy. Governor Ducey has made statements suggesting that S.B. 1164 is expected to take precedence over current Arizona abortion legislation, which indicates that the judicial bypass provision will remain.

On the other hand, Attorney General Mark Brnovich has stated that a law enacted before Arizona was a U.S. territory is expected to become the law of the state, effectively banning abortion unless the person’s life depends on it. While not an outright ban, A.R.S. § 13-3603 will drastically decrease the number of physicians willing to offer an abortion, even as a lifesaving means, out of fear of liability.

Since Dobbs, a federal district court judge enjoined the enactment of A.R.S. § 13-3603 and blocked enforcement of a 2021 statute that purported to create fetal “personhood.” The first issue, whether A.R.S. § 13-3603 will take precedence over S.B. 1164, is currently being adjudicated in Pima County, in Brnovich v. Planned Parenthood of Arizona, Inc.

Currently, there is a stay on the implementation of A.R.S. § 13-3603. This means that abortion, including the judicial bypass process, is currently available for all pregnancies that qualify under S.B. 1164 (15 weeks or less). The future of abortion largely rests in the hands of the incoming Attorney General and each County Attorney. As of November 11, 2022, the results of the 2022 Midterm Election in Arizona are yet to be finalized.

If A.R.S. § 13-3603 becomes the law in Arizona regarding abortion, the judicial bypass procedure will likely disappear alongside the right to a safe and legal abortion. Many minors, whether their pregnancy is the byproduct of rape, incest, or a simple mistake, will be forced to carry their unwanted pregnancies to term.

Conclusion

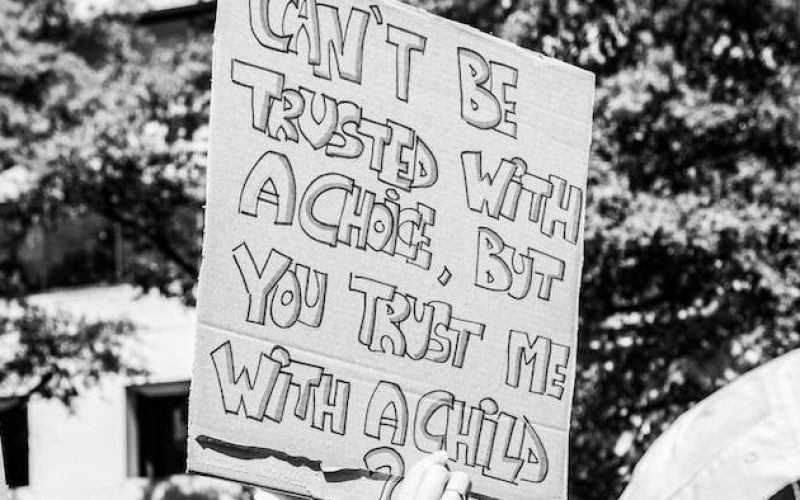

The judicial bypass process is flawed. In fact, research shows it may actually be harmful because it makes a young person navigate the legal system and justify their desire for an abortion to a complete stranger. Nevertheless, it needs to be protected. The legislature put this process into place because it has value, and it should not be abandoned in the wake of Dobbs. Critically, this process protects a portion of the population who lack a voice, both in politics and over their futures due to their minority. The children seeking out a judicial bypass understand their own personal lives best. Their reasons for seeking bypass are based on their own deeply personal nuanced interactions within their families. They must be trusted when they come before a court and indicate their only avenue for health care and agency over their own bodies is the bypass process.

Local politics have more meaning now than ever before and the topics of many midterm elections reflect that. Prior to Dobbs, state and federal governments were able to chip away at abortion law but were still bound by the doctrine of Roe and Casey. Now, without this constitutional safeguard, a simple majority on a bill can dramatically alter one’s rights over their own bodies.

[1] Underage females are not the majority of the abortion population. Mysti’s clients were often women in their 30s or 40s who were pregnant from a relationship outside of their marriage and women in their 50s who did not think they were able to get pregnant anymore.

[2] Ralph, L. J., Chaiten, L., Werth, E., Daniel, S., Brindis, C. D., & Biggs, M. A. (2021). Reasons for and Logistical Burdens of Judicial Bypass for Abortion in Illinois. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 68(1), 71–78.

Gregg Woodnick has been an attorney in Arizona for over 25 years.

Mysti Rainwater is a licensed professional counselor who used to provide therapeutic services to those seeking abortions through Planned Parenthood, which included minors.

Sheena Chiang is capital defense attorney for the Maricopa County Legal Defender’s Office, managing partner of the Law Office of Sheena Chiang, PLLC, and board member at Planned Parenthood Arizona, Inc.

Isabel Ranney is a third-year law student at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University, Associate Editor for the Law Journal for Social Justice, and law clerk at Woodnick Law.