By Ryan T. McGuire

A divorce, which Arizona refers to as a “dissolution,” can be an intimidating process. Not only is it a highly emotional process, but it also often involves more interaction with the legal system than the average person will experience in their lifetime. You may need to hire an attorney, though it is not always necessary. You may need to hire experts if the issues are complicated and require expert testimony. You will definitely need to file paperwork with the court.

A divorce is the division of two things: your stuff and your kids. Your stuff is categorized as either separate or community property. Separate property is generally anything a spouse had that predated the marriage (and has not become community property) or anything received by gift, devise, or descent. Community property is generally anything that was purchased, earned, or accrued during the marriage. Under Arizona law, this is typically divided equally, with each spouse receiving 50% of what was acquired during the marriage.

When it comes to your children, the court addresses three key issues: legal decision-making, parenting time, and child support. Legal decision-making refers to the authority to make significant life decisions for your children. The court may grant (1) sole legal decision-making to one parent or (2) joint legal decision-making to both parents. Parenting time defines how much time each parent spends with the children and outlines the visitation schedule. Child support is generally calculated based on how much each parent earns, who pays for health insurance for the children, and how parenting time is allocated.

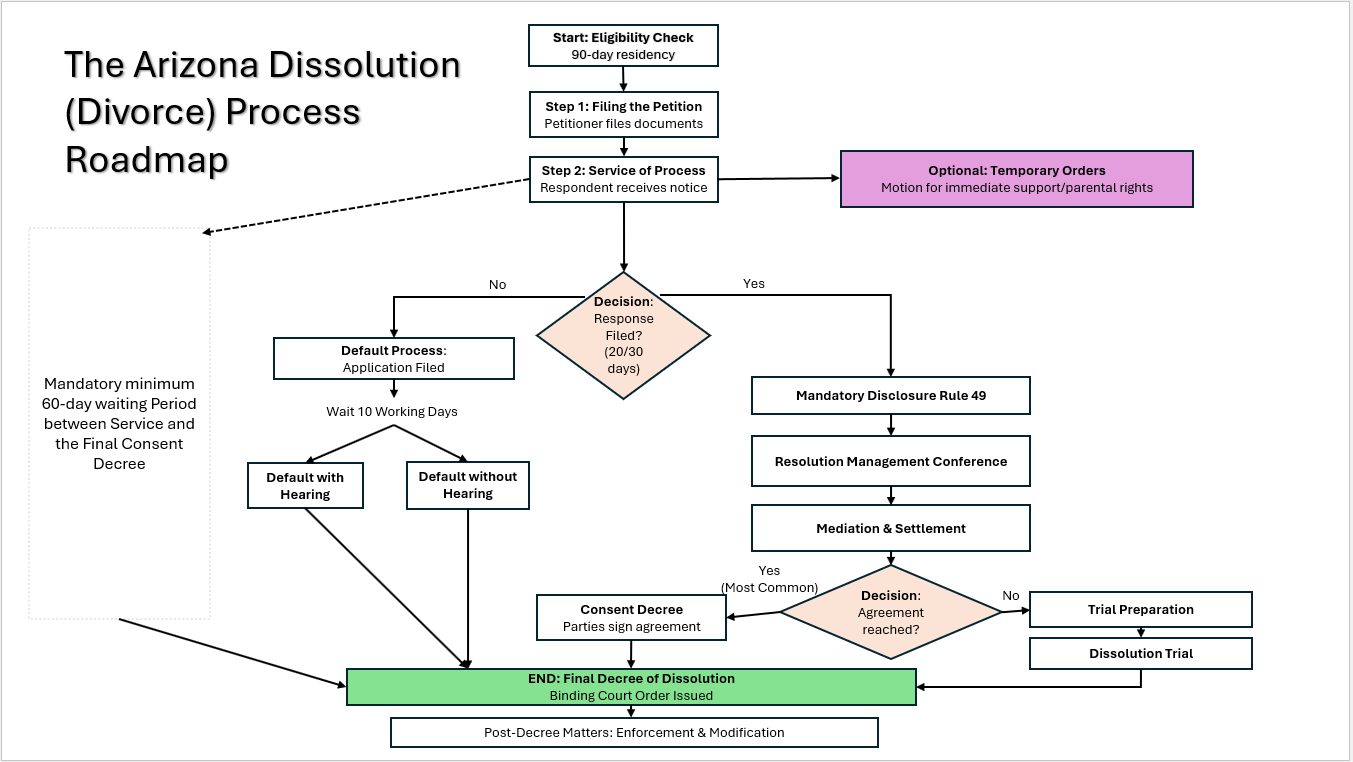

This post explains the key stages of an Arizona dissolution process from the initial filing through the final decree. It covers eligibility, required filings, service of process, temporary orders, disclosure and discovery, settlement efforts, and what may happen if the case goes to trial.

Eligibility Requirements

Arizona is a no-fault divorce state, meaning the requirement to file is solely that the marriage is “irretrievably broken,” meaning the relationship cannot be repaired. To file in Arizona, at least one spouse must meet the residency requirement, which is that either party has been domiciled in Arizona for at least 90 days prior to filing. Active-duty service members stationed in Arizona for 90 continuous days are also treated as residents for divorce purposes. Covenant marriages follow different rules and are not eligible for a dissolution grounded in no-fault.

Arizona law requires a mandatory 60-day waiting period from the date of service before any decree can be signed by the court (A.R.S. § 25-329). This means even if parties reach complete agreement immediately, the dissolution cannot be finalized until at least 60 days have passed.

Filing the Petition

A dissolution of marriage case begins when one spouse files a Petition for Dissolution of Marriage. The filing spouse is the petitioner and the other is the respondent. Core documents include the petition, summons, preliminary injunction, notice of right to convert health insurance, notice to creditors, and a sensitive data sheet. If minor children are involved, Arizona requires parties to complete a Parent Information Program class. Parties must complete this program and file their certificate of attendance before the court will sign a final decree establishing legal decision-making or parenting time. Some counties add local forms, such as an affidavit about minor children. Filing fees are paid to the Clerk of the Superior Court and vary by county. Fee waivers or deferrals may be available for those who qualify financially.

The petition must state what the petitioner wants the court to order. Common requests include division of community and separate property, allocation of debts, spousal maintenance, legal decision-making authority for children, parenting time schedules, child support, and attorney’s fees.

Summary Consent Decree Process

For parties in complete agreement from the beginning who will work together on all paperwork, some counties offer a Summary Consent Decree Process. This streamlined option allows parties to jointly file all forms together in a single packet with one court appearance and a reduced joint filing fee. The court will hold the papers for at least 60 days before reviewing and signing the Consent Decree. This process is ideal for uncontested cases where both parties can cooperate fully on preparing and signing all required documents.

Service of Process

After filing, the petition and related papers must be formally served on the respondent or the respondent’s attorney. These provide proper legal notice of the case. Service methods include:

Service by Acceptance: The petitioner gives or mails the papers to the respondent with an Acceptance of Service form. The respondent must sign the form before a notarial officer or clerk and return it. Service is not effective until the signed acceptance is filed with the court.

Service by Certified Mail: The petitioner mails papers by certified mail with restricted delivery, requiring the respondent’s personal signature. The petitioner must then file proof of delivery with the court.

Service by Registered Process Server: The petitioner hires a registered process server to personally serve the respondent at home, work, or another location. The process server must file an affidavit of service with the court.

Service by Sheriff: The petitioner contacts the Sheriff’s Office in the county where the respondent lives to arrange service. A fee applies unless the petitioner received a fee waiver or deferral.

Service of an Incarcerated Party: Service of an incarcerated party requires dual service. First, the petitioner must send papers by mail with signature confirmation. An official at the jail, prison, or correctional facility may sign for receipt. Second, the petitioner must also mail a copy directly to the inmate by first-class mail. The response period begins when the facility official signs for delivery.

Service by Publication: Service by publication is available when a party has exhausted all efforts to locate the respondent. This method requires court approval through a Motion to Serve by Alternative Service. After publication, the respondent has 50 days to respond if published in Arizona, or 60 days if published out of state.

The respondent then has 20 days to file a written response if served in Arizona, or 30 days if served outside the state. The respondent must pay a filing fee (or appearance fee) when filing a response, unless they qualify for a fee waiver or deferral. If the respondent fails to respond on time, the petitioner can file to notify the court that the other person is in default.

Temporary Orders

A dissolution case can take months to years to resolve. Temporary orders provide short-term structure while the case is pending. Typical temporary order issues include legal decision-making and parenting time, child support, spousal maintenance, exclusive use of the home or vehicles, and temporary payment of certain bills. A party requests temporary orders by filing a motion with the court. The court may hold a short evidentiary hearing to take testimony on the issues. Temporary orders generally remain in effect until a final decree or a further order modifies them.

Disclosure and Discovery Phase

Arizona requires early and automatic disclosure. Rule 49 of the Arizona Rules of Family Law Procedure mandates that each party serve initial disclosure within 40 days after filing the first responsive pleading. Disclosure is ongoing and supplemental disclosures must be served within 30 days of discovering new relevant information. The disclosure obligation is an ongoing one that continues until a final Decree or Order is entered.

Disclosure differs from discovery, which is not automatic and is only required upon request from the other party. Most cases will not require discovery beyond what is automatically disclosed under Rule 49.

Required disclosures depend on the contested issues. For example, a case involving child support disputes may require an Affidavit of Financial Information, three years of tax returns, current pay stubs, and proof of insurance premiums and childcare costs. Property division cases may require real estate documents, six months of bank statements, retirement account statements, business tax returns, and personal property lists. For parenting time cases, the disclosure could include the disclosure of protective orders, treatment providers, criminal history, and Department of Child Safety investigations. Each case will have its own disclosure requirements.

Beyond mandatory disclosure, parties may use the discovery process to get information. This includes requests for production, interrogatories, requests for admission, depositions, and subpoenas. Witnesses must be disclosed at least 60 days before trial. Disclosure documents are served on the other party but not filed with the court. This stage builds the record for negotiation or trial and helps identify hidden assets or disputed financial issues.

Resolution Management Conference

Many Arizona courts schedule a Resolution Management Conference early in the case. At this conference, the judge reviews which issues are agreed upon or disputed, the parties and attorneys may discuss settlement possibilities, and the court sets deadlines for disclosure and discovery. Some courts require a written Resolution Statement before the conference. The RMC helps shape the path toward settlement or trial and can clarify what evidence or expert opinions may be needed if the case proceeds.

Mediation and Settlement Attempts

Most Arizona dissolutions end in settlement rather than trial. Mediation or other settlement processes can reduce costs and delays, give parties more control over outcomes, and lower emotional conflict, especially where children are involved. Mediation may be private or through the local courthouse. During mediation, a neutral mediator helps spouses discuss property, support, and parenting issues. Attorneys often prepare settlement proposals and attend sessions to protect their clients’ interests.

If the parties reach full agreement, they submit a signed consent decree or settlement agreement to the court. When parties submit a Consent Decree, the judge must rule within 21 days of filing the Notice of Lodging, or 81 days from the date of service on the respondent, whichever is later. The judge has discretion to accept or reject the decree, or to schedule a hearing for both parties.

Default Hearings and Decrees

When a respondent fails to respond and the petitioner proceeds by default, the process varies depending on whether a hearing is required. The petitioner would file an “Application and Affidavit for Default.” After filing the Application and Affidavit for Default, the petitioner must wait 10 working days (excluding weekends and court holidays) before submitting the proposed decree to the court. After this waiting period, the respondent has 10 days to file a response. In most situations, the petitioner can get a default decree without a hearing. However, the court may still require a brief default hearing, particularly when children or significant property are involved.

Situations Requiring a Default Hearing: A default hearing is required if (1) the respondent was served by publication; (2) the respondent is a minor or incompetent; (3) the respondent doesn’t live in Arizona and the parties weren’t married in Arizona; or (4) the petitioner requests a decree different from the petition without a written separation agreement.

Default Hearing Process: In counties like Maricopa, parties must submit their proposed decree and required forms to the Family Department for review before a default hearing will be scheduled. Submission can be by email or in person. The Family Department will review forms within 3 business days and contact the party to schedule a hearing if the forms are ready, or provide instructions on corrections needed. Default hearings are typically conducted by video. The default hearing will be set at least 60 days from the date the respondent was served the divorce papers.

Default Decree Without Hearing: In all other situations, the petitioner may request a decree without a hearing by filing a Motion and Affidavit for Default Decree without Hearing. The court cannot sign a default decree until at least 60 days has passed since the date the respondent was served.

The petitioner must prepare a default decree that repeats as closely as possible what was requested in the petition. If the decree differs from the petition, the petitioner must have written consent from the respondent or file an Amended Petition.

Trial Preparation if Settlement Fails

If issues remain unresolved, the court sets the case for trial. Preparation often includes drafting a detailed pretrial statement with each party’s positions and legal theories, organizing exhibits, preparing witnesses, and coordinating expert witnesses if applicable.

The Dissolution Trial

Arizona dissolution trials are heard by a judge. At trial, both spouses testify, along with any lay or expert witnesses. Evidence is presented, and the attorneys make legal arguments.

After the final trial, the judge issues a Final Decree of Dissolution that decides property division, debt allocation, spousal maintenance, legal decision-making, parenting time, and child support. (Note: specific timelines for issuing the decree may vary by county and case complexity.)

Post-Trial Matters

The final decree is a binding court order. After trial, parties may need to divide accounts, transfer titles, refinance debts, implement parenting time schedules and support orders, or use wage assignments to collect child support or spousal maintenance. If there are issues, parties have various post-decree filing options available.

Conclusion: A Roadmap, Not a Shortcut

The above process provides a general overview of the path dissolutions can take. However, each case, like each client, is unique and requires special attention from the right attorney. High-conflict parenting disputes, complex business valuations, or allegations of hidden assets can stretch a case well beyond the typical timeline. Understanding the process does not replace the benefit of experienced counsel, but it does help people make informed choices and set realistic expectations as they navigate one of life’s most difficult transitions.

Author

Ryan T. McGuire is a law clerk at Woodnick Law PLLC and a second-year student at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. He leverages his master’s degree in philosophy to produce thorough legal research and writing, with a focus on family law matters. Ryan brings a strong foundation in legal analysis and academic interests spanning family, juvenile, and criminal law.