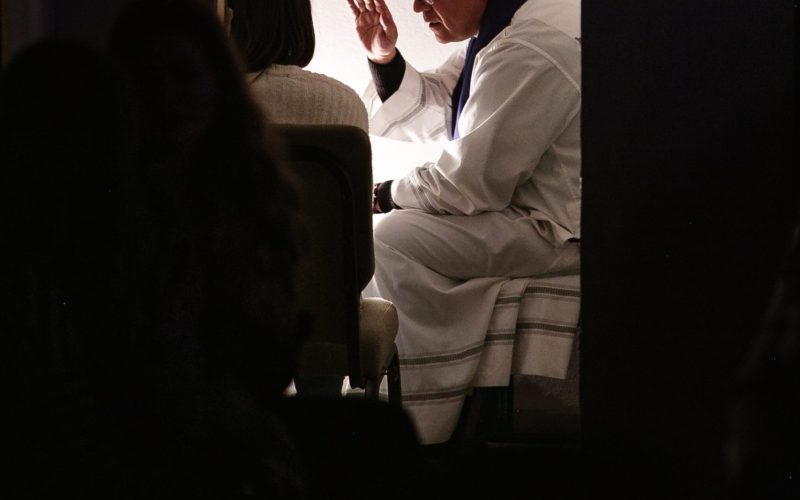

The conversation between an individual and a member of the Clergy during a spiritual confession is sacrosanct. It is a time when the person confessing should feel that they can speak freely, without fear of reprisal. This act of confession is so valued that Arizona law permits members of the Clergy, who are statutorily mandated reporters, to withhold information obtained during the confession. A.R.S. § 13-3620 (A). But even then, there is a caveat. Some confessions, such as the one by a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saint (LDS) in Cochise County, are too egregious to remain privileged.

Background

In 2010, Paul Douglas Adams first confessed to Bishop John Herrod, who was also the family physician, that he was sexually abusing his daughter, MJ, who was just 5 years old [1]. Instead of reporting the abuse to the police or child welfare officials, Bishop Herrod called the church “help line,” who advised him to remain silent. MJ would continue to be abused for at least 7 more years, as would her little sister, who would first be abused when she was just an infant. It is unclear if Adams abused his other four children [2].

Adams, a Border Patrol Agent at the time, continued to inform Herrod about the abuse, which Adams had started videotaping and uploading to the internet. Herrod brought MJ’s mother, Leizza Adams, into the counseling sessions, hoping she could do something to stop the abuse [3]. When that failed, Herrod spoke to a second Bishop, who incorrectly told him that he was required to keep quiet under the mandatory reporting statute, A.R.S. § 13-3620. A confidential disciplinary hearing for Adams took place and he was ex-communicated in 2013 but at no point did anyone in the Church report the abuse to law enforcement or DCS [4].

The abuse did not stop until Adams was arrested in 2017, and it was not because someone at the Church reported him. Rather, Adams was only arrested after law enforcement in New Zealand notified the Department of Homeland Security after they discovered a video of child pornography, which was traced back to Adams’ computer. A subsequent search of the Adams’ home recovered thousands of “videos depicting child sex abuse, many featuring the Adams daughters” [5]. Based on the insurmountable amount of evidence tying him to the sexual abuse, Adams was federal indicted.

But Adams would ultimately not be punished for the abuse. A few months after he was indicted, Adams completed suicide while incarcerated. Adams’ wife, Leizza, who knew about the abuse for years and did nothing to prevent it, pled no contest to crimes related to enabling and covering up the abuse. She was sentenced to two and a half years in prison and was released in 2020 [6]. She has not regained custody of the children.

In the aftermath, the LDS Church and several named members, including Bishop Herrod, were sued by three of the Adams children for negligence and conspiring to cover up the child sexual abuse to “avoid ‘costly lawsuits’ and protect the reputation of the church” [7]. The lawsuit is still ongoing.

Arizona Law

Although Arizona’s mandatory reporting statute does permit members of the Clergy, priests, or Christian Science practitioners to refrain from reporting a “communication or confession,” this is not all encompassing. The group member may only refrain from reporting the information if they determine “it is reasonable and necessary within the concepts of the religion.” Id. Not to mention, the statute only permits, it does not mandate. There is no restriction on what can be reported. Whether and what to report is within the discretion of the clergy member – who can arguably evade the mandatory reporting duty by deciding that withholding is “within the concepts of the religion.” I.e., if a church member confesses to having murdered a child, that confession could remain privileged if the clergy member decides the import of a private confession is more valuable to the religion than the result of making a report.

The “misunderstanding” of the Clergy-Penitent Privilege that led to Bishop Herrod and those working the “help-line” at the Church had severe consequences. Two children suffered atrocious abuse that was known by their mother, trusted members of their Church, their Bishop/Family doctor, and even members of the Mormon church in Salt Lake City, Utah. Their trauma is irreversible.

It is vital that mandatory reporters like members of the Clergy, understand that their duty to report child abuse and neglect may be incompatible with their religious practice of keeping confessions private [8]. It is a conflict that must be overridden by a duty to ensure the safety and well-being of children, lest extreme abuse like the Adams’ children be permitted to occur. Persons with religious duties would be well advised to comply with their duty as a mandatory reporter and report suspected abuse or neglect to DCS and/or local law enforcement.

[1] https://apnews.com/article/Mormon-church-sexual-abuse-investigation-e0e39cf9aa4fbe0d8c1442033b894660

[2] Id.

[3] https://www.12news.com/article/news/national/utah-lawmaker-told-mormon-bishop-not-to-report-abuse-in-arizona-records-show/75-b185b0b3-d79f-4cc7-b4ba-12a5b0093db8

[4] Id.

[5] https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona/2022/08/04/mormon-church-sexual-abuse-help-line-paul-adams/10234183002/

[7] https://apnews.com/article/Mormon-church-sexual-abuse-investigation-e0e39cf9aa4fbe0d8c1442033b894660. The lawsuit against the LDS Church is not just limited to the Church in Cochise County, but extends to the Church headquarters in Salt Lake City, Utah. The major theme of the lawsuit is that the Church (1) had knowledge of the abuse, (2) had an opportunity to report the abuse, but did not, and (3) encouraged others to remain silent, thereby permitting the abuse to continue.

[8] It should be noted that, according to the text of A.R.S. § 13-3620(A), members of the Clergy is not an all-encompassing term. Also delineated as a mandatory reporter are Priests and Christian Science practitioners. It is unclear why the statute uses three separate terms instead of the general “Clergy.”

Gregg Woodnick has been an attorney in Arizona for over 20 years. He has trained many mandatory reporters, including doctors, physician assistants, mental health workers, educators, and (one time) the Catholic Diocese.

Isabel Ranney is a third-year law student at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University, Associate Editor for the Law Journal for Social Justice, and law clerk at Woodnick Law.

Also in this series: A Position of Trust: Teachers Accused of Sexual Misconduct with Students | A Position of Trust II: Teachers Facing Prosecution